As part of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) – funded Research Grant project “Continuity and change in the transmission of musical knowledge in early 20th Century Ottoman Egypt: The case of Amin Al-Buzari “.

Bashir Saade – The University of Stirling

Listening, performing and recording early Egyptian music

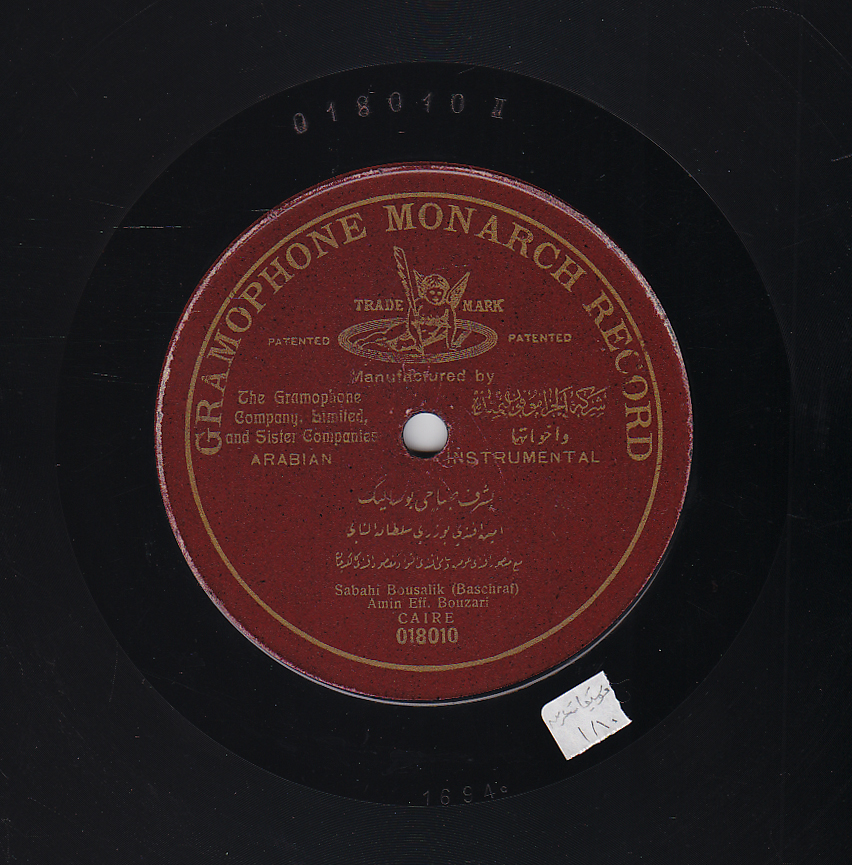

Between June 16 –18, 2025, the Takht (traditional Arabic musical group) ensemble of Oxford Maqam gathered in the Beyond 1932 Project Room at Kings College London’s Music department to propose new renditions of select instrumental pieces from the Arabic and Ottoman repertoire. The sessions focused on the works performed by reed-flute nay player “Neyzen” (نيظان) Amin Buzari (1847–1928) and other musicians of the early 20th century Egyptian music scene. The early 1900s-1920s was a period of flourishing musical recording and publishing. A multitude of companies such as Gramophon, Odeon, Baidaphon, Polyphon, Zonophone, and others competed over a vibrant scene of talented Cairo-based musicians and singers.

Listening and performing these pieces was an invitation to reflect on several key aspects of this sound archive: The particularity of the recording technology of the time, the style of playing and its relation to more general understandings of Maqam, Tarab, Arabic and Ottoman music, and lastly the specific idiosyncrasies of the musicians performing: Amin Buzari, the violinist, Sami al Shawwa (1889–1965), the Qanun players, Abdel Hamid al Quddabi and Maqsoud Kilikjian, as well as the Oud player, Mansour Awad.

GRAMOPHONE MONARCH RECORD – Courtesy of AMAR Foundation Archives, Kamal Kassar Collection

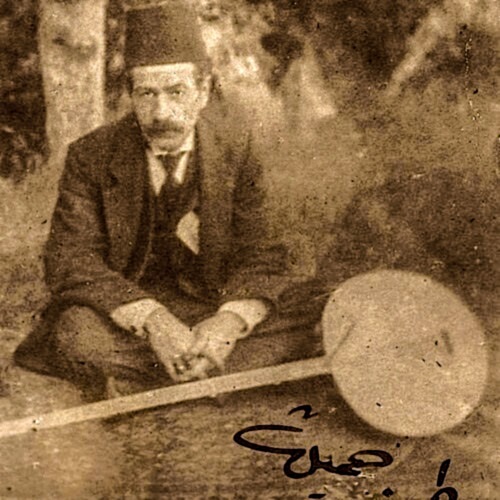

Amin Buzari, a semi-blind Egyptian musician of Armenian descent, who appears to us through these early 20th century recordings is a witness to the cosmopolitan and culturally diverse universe of late 19th century Ottoman society. With different configurations of musicians, Buzari recorded a few Bashraf (Peşrev in Turkish) and a Semai, in 1909–1910 for Gramophone, and later for Polyphon in the mid 1920s. These instrumental pieces are typically considered to be part of the Ottoman repertoire, loosely representative of a highly diverse sets of city-based traditions, from Istanbul, Aleppo, and Cairo, to name a few, across Arabic, Turkic, and other regions and influences.

Buzari and his takht’s recordings are precious for several reasons. They capture a way of performing this repertoire that has mostly disappeared—one that is markedly different from the more recent “Arabic” or “Turkish” renditions of today. Moreover, as a Neyzen of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and dubbed by his contemporaries as the “Sultan of the Nay”, Buzari is part of a rare breed of musicians: the nay as a solo or lead instrument mostly disappears after the 1920s, only to reappear in larger orchestral forms as a ‘folkloric’ or ‘traditional’ fetish with no musical autonomy.

The pieces we focused on, all found in Buzari’s recordings, are a mix of Istanbul and Cairo-based composer works along with some from Arabic traditional repertoire:

- Bashraf Sabahi Bosalik

- Bashraf Khozam Segah Osman Bey (1816 –1885)

- Bashraf Qarabatak Segah (Hızır Ağa)

- Tahmila Rast, Marsh Abbas Hilmi (composed by Luppa Bey)

- the Egyptian Shanbar Hijaz, Kemani Ali Ağa’s Shehnaz Peshrev (1770 –1830) Watch the video here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ru6kh-4cIo

- Semai Nihavend Neyzen Yusuf Pasha (1821-1884). Watch the video here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFH8jyrceM0

The differences between the various ways these pieces are performed between Istanbul and Cairo is made greater by the fact that the lead instrument in these recordings is the nay.

GRAMOPHONE MONARCH RECORD – Courtesy of AMAR Foundation Archives, Kamal Kassar Collection

For example, the pre-World War I rendition of Buzari’s Takht bears little resemblance to how the Shehnaz Peşrev or the Bashraf Qarabatak Segah are played in the recordings we hear from more recent Istanbul-based musicians. Interestingly, the earliest recordings we have of these Peşrevs, from Istanbul-based musicians, is by the great Tanburi Cemil Bey whose version, recorded in 1907, more closely resembles those of his Egyptian contemporaries, when compared to the more recent Turkish renditions of this piece. Yet it still differs markedly. This points to the fact that, not only were their different traditions of performing these pieces across Ottoman cities of the early twentieth century, but that the post Ottoman setting saw a widening of this difference with subsequent nationalist projects.

Pitch and other considerations

Our takht was composed of Tarik Beshir (Oud), Sophie Frankford (Violin), Martin Stokes (Qanun), Bashir Saade (Nay), and Walid Zeido (Riq). Pitch was one of the issues that we considered throughout listening and attempting to perform. Buzari’s playing is notoriously higher pitched than convention would have it in more recent renditions of these instrumentals. It is hard to know whether Buzari actually played in that pitch outside of the recording setting, or whether the shellac-based recording technology of the period might have made nay players favour higher pitched instruments in order to leave an acoustic trace. Examining more broadly the recordings of that time, it seems clear that singers and some other instrumentalists did perform on higher pitch than the later C or D piano standard. If anything, the lowest pitch in most of the recordings, especially before World War I, was E or Buselik, and seemed to mirror the standard Istanbul-based Ottoman one. Noteworthy here is that many of Buzari’s solo improvisations are in E or F most of his group works are in G and higher. The most common though is around G / F which may be another tuning version of Nawa (G) than the contemporary standard A440 one.

For a contemporary Arabic ensemble, like the Oxford Maqam, that is used to playing in Rast or Dogah tunings, playing Bayati or Hijaz maqam in G proved to be challenging— especially in terms of coordinating the range of playing for each instrument. Performing these pieces in this range, however, did clarify some of the dynamics taking place in these early recordings, where the Qanun (or Oud) seemed to take on a foundational rhythmic role, the violin a mid-range in terms of pitch—drawing on the basic broad strokes of the melody—with the nay as the lead and most high-pitched instrument. In that sense, the nay seemed to emulate the voice as found in other recordings of that time.

For Oud player Beshir, “Playing Saba from G and Segah from B half flat allowed the oud the opportunity to play on the lower registers at times to contrast the qanun and Ney’s higher register playing. With the Violin sitting pretty in its md range in this arrangement i feel it allows for the ney to come through quite well and still have a full spectrum of sound to give the pieces the depth of sound they need”.

For Qanunist Stokes, the issue was not so much about transposing but the structure of the recording process. Electric recording with one mic involves musicians placed in a close up way, whereas shellac recording, the way Buzari and his takht recorded, involved the Oud being very close to the horn that records the sound with the Qanun situated much further away. Drawing from recording previously with Oxford Maqam in a shellac recording studio a few years ago, Stokes notes that this gave him “a lot more freedom and headspace” to hear his instrument than the electric recording setup we had at Kings.

Violinist Frankford notes: “In terms of the pitch, it felt a little higher than I’m used to playing but was totally comfortable still, I just sometimes found myself running out of notes at the top so had to jump down the octave (in my Arabic music experience I generally never need to play higher than 3rd position. In Western classical it’s very common to play higher than 3rd position so I’m used to it just not so much in this context. I was using the recordings as a guide when to play up or down the octave; it felt like it needed some kind of bassy notes from the qanun/oud when the nay and violin were both playing high”. Frankford notes also that it may be that changing the tuning of the violin would fit better this kind of pitch: “I use the now-standard Arabic tuning – GDGD – but I wonder about playing around with what (I believe) used to be an alternative common tuning – GDGC – and how this might change how different maqams fall under the fingers. I haven’t listened closely enough to the recordings but would probably be able to hear when Shawwa is playing open strings to help figure out the pitch / his tuning.”

The recordings of Amin Buzari that are used for this research were provided by AMAR Foundation.