To define an identity is often to betray a tradition.

Reflections on Prof. Jean Lambert’s lecture, 11 June 2025, King’s College.

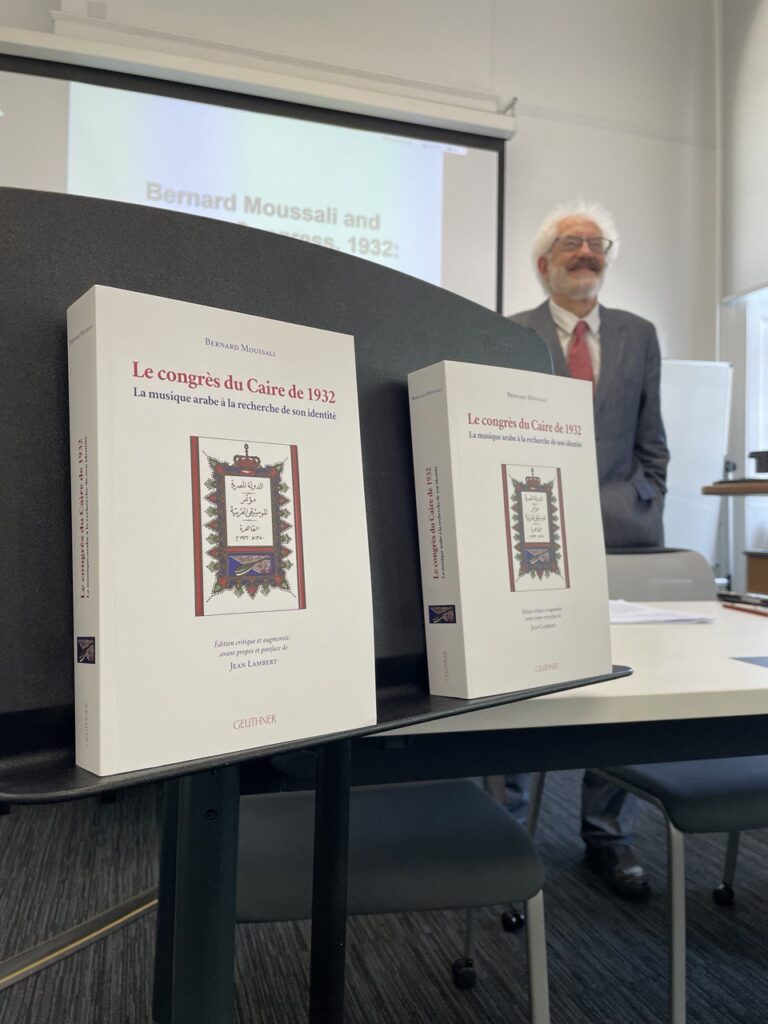

This paradox hung in the air as Professor Jean Lambert took to the stage on June 11th, weaving history, musicology, and memory into a single resonant thread. His lecture, titled Bernard Moussali and the 1932 Cairo Congress: Arabian Music in Search of its Identity, was not only a tribute to the pioneering legacy of Bernard Moussali, but also a haunting meditation on the unfinished debates that still shape Arab music today.

Hosted as part of the 1932MusCon initiative at King’s College London, the event marked more than a scholarly commemoration. It was, in effect, a public séance—calling back the ghosts of a century-old congress that had dared to ask: What is Arab music? Can it be modern and still be itself?

A Congress of Contradictions

Held in Cairo between March and April 1932, under the patronage of King Fuad I and the orchestration of Baron d’Erlanger, the Congrès de musique arabe sought to define, archive, and perhaps reinvent Arab music for the modern era. It assembled a constellation of artists and intellectuals—among them Béla Bartók, Alexis Chottin, and Muhammad al-Qubanshi—across the lines of empire, region, and discipline. What emerged, as Lambert explained, was less a consensus than a cartography of fracture.

The Congress exposed tensions between modernists, who championed mass media and Western instruments, and traditionalists, devoted to tarab and improvisation. Even deeper were ideological rifts, especially the uneasy dominance of Egyptian musicology over Levantine and Maghrebi contributions. “We must remember,” Lambert emphasized, “that the expression ‘Arab music’ barely existed before the Congress. People spoke of ‘Oriental music’—the shift in terminology was already a political gesture.”

The Archival afterlife

Lambert’s lecture revolved around the posthumous publication of Moussali’s unfinished doctoral work, now released as Le Congrès du Caire de 1932 (Geuthner, 2024). As editor and co-author, Lambert spent over two decades completing the manuscript. “It’s not just Moussali’s book,” he admitted with candour, “but a shared labour. Much of what appears in brackets or quotation marks is mine—but the soul is his.”

Through detailed visual slides and rare audio excerpts, Lambert recreated the Congress’s sonic and symbolic world. From the recorded voices of Jewish Iraqi instrumentalists and Coptic chanters to women wedding singers and forgotten Moroccan rabab players, the Congress’s 78 rpm archive revealed a polyphonic map of Arab musical identity—one already fragmenting even as it was being preserved.

Lambert dwelled particularly on ‘the discreet nay player’, Ali al-Darwish of Aleppo, whose Ottoman-rooted repertoire and theoretical training quietly reshaped the Congress’s debates, despite his almost complete silence in the official proceedings. “His role was invisible,” Lambert noted, “yet pivotal. He brought Syria to Cairo without ever being heard.”

The Battles over Scale and Sound

One of the most charged debates, Lambert recounted, concerned the Arab musical scale. Should the Congress formalise the now-iconic 24 quarter-tone system, or preserve the lived flexibility of microtonal traditions from Cairo to Aleppo? Lambert traced the contested genealogy of the quarter-tone idea, even citing an obscure 18th-century French Orientalist—an insight that complicated the oft-repeated origin story tracing it to Mashaqa.

Instruments too became battlegrounds. The violin, recently Arabized by Egyptian virtuosos, was accepted; the piano, symbol of Western hegemony, was rejected. And yet Alois Hába, Czech theorist of quarter-tone harmony, was present in the audience, pressing for a universal, modern music. “It was,” Lambert reflected, “a musical Babel—a sincere, chaotic search for form.”

Afterlives and Silences

The Q&A, rich and layered, illuminated further blind spots. Why were Gulf musicians absent? Because, Lambert explained, “the Congress sought ‘learned’ urban music—oral traditions in the Peninsula weren’t even recognised as part of the field.” What of the vast muwashshahāt corpus shared between Syria and Egypt? “Its path,” he replied, “was reciprocal, but its recognition was not.”

Several audience questions explored the gendered silence of women musicologists at the Congress, with Lambert acknowledging recent research into overlooked figures such as Brigitte Schiffer. “Many were there. Few were recorded. Some were erased.”

A final intervention asked why so much of the Congress’s material—recordings, reports, debates—has faded from public memory, especially in Egypt. “Ironically,” Lambert answered, “many of those sounds were old-fashioned even in 1932. It was already the ‘swan song’ of an era. Abdel Wahab was there, but not happy—he represented the new music waiting impatiently at the door.”

Toward a New Reformism?

In closing, Lambert offered a provocative reading: Could the Congress be reinterpreted not as failure or nostalgia, but as a reformist compromise? A model for how traditional oral cultures can enter modernity without disfiguring themselves?

“It’s a question,” he said, “the book cannot answer alone. But it must be asked again—perhaps by your generation, through this very project.”

And with that, the music faded, and the midsummer sun lingered just a moment longer through the windows at King’s.

Abbas Alsadeq – PhD student, King’s College